Something different this time: a joint post with writer friend and fellow Substack scribe Monika Ullman. Like me, she was a longtime contributor to the late Vancouver Courier, Canada’s largest-circulation community newspaper. We met up in the city recently and our conversation took us into the weedy territory of “conspiracy theories” and “conspiracy theorists.” How did these become such an all-purpose terms of official contempt? We decided a full answer would require two - maybe three - joint posts on Substack.

Monika Ullman: Living as we do in a time of angst and paranoia, it’s no wonder that a majority of North Americans believe that 9/11 was an inside job, and that the assassination of the Kennedy brothers was a conspiracy between the CIA and certain mobsters as well as people in the State Department who hated everything about the Kennedy brothers. You might say that these are the ‘reasonable’ versions of CT, not to be confused with the flat-earthers and people convinced that giant lizards rule us. It’s remarkable how nobody is bothering to make this distinction. On social media and in the legacy press, a Conspiracy Theorist equals Moron, big M. Few if any people have the fortitude to face such public denigration.

Geoff Olson: “Conspire” literally means “to breathe together.” There really shouldn’t be anything all that controversial about the notion of conspiracy, whether in theory or fact. Even the 18th century proto-economist Adam Smith thought it humdrum. “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices,” he darkly insisted.

I’ve long been fascinated how the tag-team terms, “conspiracy theories” and “conspiracy theorists” appear to have little descriptive utility, but work very effectively to discourage intelligent adults from thinking - much less talking publicly - about controversial or fringe topics. One thing that makes them both nonsensical and effective is how they conflate claims that have no necessary relation, like say 9/11 and flat earth theory.

It’s remarkable how these terms first gained serious traction in the media after they appeared in an Apr. 1, 1967 CIA report entitled, “Countering Criticism of the Warren Report,” which was declassified by the agency in 1996.

Conspiracy theories have frequently thrown suspicion on our organization, for example by falsely alleging that Lee Harvey Oswald worked for us. The aim of this dispatch is to provid material for countering and discrediting the claims of the conspiracy theorists, so as to inhibit the circulation of such claims in other countries.

And how was this to be accomplished? Various means were suggested.

To discuss the publicity problem with liaison and friendly elite contacts (especially politicians and editors), pointing out that the Warren Commission made as thorough an investigation as humanly possible, that the charges of the critics are without serious foundation, and that further speculative discussion only plays into the hands of the opposition. Point out also that parts of the conspiracy talk appear to be deliberately generated by Communist propagandists. Urge them to use their influence to discourage unfounded and irresponsible speculation.

Another ploy is “to employ propaganda assets to answer and refute the attacks of the critics. Book reviews and feature articles are particularly appropriate for this purpose.”

Here’s two screenshots of a Google ngram count of the term conspiracy theories and conspiracy theorists respectively, in printed publications up to 2020. Though ngram indicates a tiny signal right back to the late 1800’s for the first and to the 1940’s for the second, their usage intriguingly lifts off in the late sixties and goes exponential beginning in the eighties.

So although the spy agency didn’t invent the terms, they certainly appeared hellbent to privately communicate their importance to politicians, media figures and “propaganda assets.” Looks like it worked.

Ergo, what seems to be an actual conspiracy involving the terms, “conspiracy theories” and “conspiracy theorists.” How meta is that?

Monika Ullman: Even supposedly brilliant people get confused and agitated by this subject, especially if they happen to reside in an Academic tower somewhere. Indeed, there is an entire cottage industry earnestly digging into why there seems to be an explosive rise in CTs. Strangely, they never ask if it might have something to do with the shocking failure to respond with something like intelligence to the pandemic and the subsequent betrayal by the people we once trusted: doctors, the entire health care sector and parts of science itself. Something must be done! A rather typical example of what is being done is the BBC doing its best not to appear extremely biased (and failing):

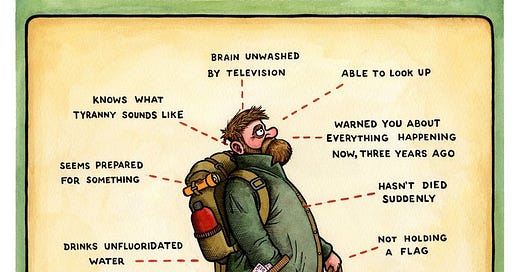

Geoff Olson: For the past sixty years, the uber-embarrassing scarlet letters of CT have successfully discouraged many academics, journalists and the lay public from pursuing deeper structural analyses of power relations. Generally, there’s a simple recipe for a managing editor or commentator-for-hire. Take a straightforward claim - for example, that it’s impossible for the steel frame high-rise Building No. 7 in New York to have collapsed on its own footprint from fire alone. Refuse to examine the claim itself. Just mix the term ‘truthers’ in with jokey references to faked moon landings, the flat earth, or maybe even world control by shape-shifting reptoids from the fourth dimension. Set to simmer in a stew of ad hominem remarks, with a pinch of pop-psychology posturing. (‘Those tinfoil hat-wearers with their rampant cognitive biases!’)

Alternatively or additionally, poke tentatively at the wild claim with a stick of straw man arguments, before tossing it into the compost bin.

The “Thing One” and “Thing Two” of conspiracy management are cover stories and mockery.

You mentioned the BBC. Just as in Britain with the Beeb and vehicles like The Guardian, the legacy media in America has its boutique publications and portals for the educated liberal left - such as The New Yorker and The Atlantic and PBS, all of which actively dismiss what they deem to be “conspiracy theories,” regardless of any empirical merit. These are online and offline information silos favoured by the kind of people who pride themselves on being smarter than everyone else, as well as being above the social media fray. In other words, the types you want buy in from, because they represent a large fraction of the managerial and communications class. What were once described as the petite bourgeoisie - the ones in between the proles and the owners of the means of production.

So when these intelligent but well-propagandized people parrot the term “conspiracy theories,” they’re almost always sincere, in spite of any cognitive dissonance!

I consider the legacy media properties they follow, including those on the “right,” as epistemological walled gardens. Meaning that from within the inside, you get an expansive view of things expertly arranged and manicured. You may never even suspect that the real plants have convincing plastic ones sprinkled among them for decorative purposes.

Outside the walled garden is the scary, largely undocumented wilderness of covert operations, bank cartel money laundering, offshore accounts, arms running, psychological warfare, mind control, fringe phenomenon, media manipulation and dirty deeds of Netflix-worthy depravity. Only very occasionally is some strange exotic plant, like the Epstein case, brought into the walled garden for a brief public display. (And in the case of Netflix, the recent Danny Casolaro documentary, which addresses a case now safely decades in the past.)

From within the perspective of the garden, there are only occasional hints of powerful circles within and without government exercising dangerous schemes for immense profit. Some politicians and industrialists get up to shenanigans that get exposed, for sure, but there are certainly no plots by shadowy cabals that can alter the course of history.

No, the historical record is simply ‘one damn thing after another’, with nation states stumbling from war to war and recession to depression and back. Most unfortunately, the world is blown about by the winds of inflationary spirals, bad leadership, and serial threats from rogue states, terrorists, and infectious diseases.

These are not at all completely false claims, it’s just that they don’t offer a fully functioning model of how the world really works. Instead, news consumers are instructed that all will be well in the garden if they have faith in our media-endorsed expert class with its think tanks and ES&G protocols and in-house definition of “misinformation.” Oh, and along with the trusty pesticide of voting using the candidates of their - I mean, our - choice.

The garden isn’t outside that wilderness, but embedded in it. And it’s porous; the manufacturers of consent made the walls out of state propaganda rather than concrete blocks. These walls of information are there not so much to keep the wilderness out, but to convince the garden-goers there isn’t much of a wilderness out there to begin with. And the majority of them are eager to believe it. (Hell, I’d prefer to believe it!)

Monika Ullman: I agree, but I think we need to dig into the psychology of the walled garden a bit more. That’s a very useful metaphor because it highlights an underappreciated aspect of this entire discussion: the normal human desire to live in a ‘safe space’, which is what a walled garden is, and the extreme emotional cost of venturing into wild reality and admitting that conspiracies exist along with theories about them. Psychologists call this process denial and note that dealing with it is difficult while the public has adopted the term as a bad joke: denial is a river in Egypt, don’t you know.

This joke is an attempt to defang the sense that the world is fraught with danger and uncertainty. And because most people prefer to be happy, they strenuously deny their existence. But you can’t talk about walled gardens and safety without talking about trust. It seems to me that you will never voluntarily venture beyond the wall unless things go very wrong inside the garden, when everything starts to die and is overrun with intellectual weeds. When cognitive dissonance takes over, you begin to lose faith in the garden’s management. That is what has happened to large numbers of people as they discovered the lies fundamental to the entire pandemic narrative.

At the same time, another large group has strenuously objected to even noticing the decay in the garden and keeps insisting that anyone who does so is a conspiracy theorist. Which leaves one question: most people who continue to believe the official propaganda are blameless, so what’s stopping them from re-thinking the pandemic?

I believe it goes beyond the embarrassment of knowing you’ve been duped; it involves changing one’s entire world view, of admitting that the world we thought we lived in is at best a benign fantasy and at worst, an organized lie. In other words, unsafe and often, unfathomable.

A brilliant examination of the emotional cost of such a realization occurs in Lawrence Durrell’s novel Mountolive, in which the writer Pursewarden, likely Durrell’s alter ego, is working for the British embassy in Alexandria. Quite by accident, he discovers that there is a full blown conspiracy masterminded by his close friend, Nessim Hosnani, a wealthy Coptic Egyptian. Nessim went to great lengths to convince him that he wasn’t in fact importing enormous amounts of weapons into Egypt and fomenting a violent uprising, as one of the other officials at the embassy discovered.

In his suicide note to David Mountolive, the Ambassador, Pursewarden lays out his reasons and describes his bleak realization that the world wasn’t as he imagined and that acting on this knowledge means not only losing a friend but also, orchestrating his downfall:

My dear David

…I stumbled upon something which told me that Maskelye’s theories about Nessim were right, mine wrong…but I simply am not equal to facing the simpler moral implications raised by this discovery. I know what has to be done about it. But the man is my friend…Ach what a boring world we have created around us. The slime of plot and counterplot. I have just recognized that it is not my world at all. (I can hear you swearing as you read).

I feel in a way a cad to shelve my own responsibilities like this, and yet…I know that they are not really mine, never have been, but they are yours. And jolly bitter you will find them.

You must act…Mine however not to reason why. I’m tired, my dear chap; sick unto death, as the living say. And so…

Not everyone has such a finely tuned moral sense, but I think that the personal fallout from taking a stand, or even changing one’s mind, can stop anyone from taking on a fight like this. I’m not saying that the pandemic was a conspiracy; what I am saying is that there is an urgent moral case for a closer examination of the facts. At the moment, what we have is a society living in widespread denial. It’s called a ‘defense mechanism’ for a reason.

Just to be clear, what is a “Conspiracy Theory?” According to an article published by the University of Chicago, it is ‘a group of powerful people working together to accomplish a goal they are trying to keep secret and acting at the expense of others.’

Actually, that’s a definition of a conspiracy, period, without the theory part. The theory is simply a story cobbled together from available data, a story someone is trying to keep secret, one that reveals a group of people or an individual guilty of doing dark deeds.

While delving into the research, I began to realize that this subject is a hydra-headed monster leading back in time to the Freemasons, Wikileaks, and forward to what AI actually does and how it works. AI looks for patterns and anomalies in patterns. That is exactly what a human mind does when trying to make sense of the world. It is the anomalies that bother us because that is where the hidden conspiracies lurk. Where things don’t add up to a coherent picture. AI looks for secrets hidden in the data, in other words, a conspiracy. And that is why the really intelligent people I have read are all in on the subject of Conspiracies, though not on the truly nutty conspiracy theories.

Geoff Olson: Yet do we have any Calipers of Truth to objectively separate the “truly nutty” from the darkly likely? For example, I know someone who bought into flat earth theory for a stretch because “well, they lied to us about Covid.” Such a believer may be easy to dismiss, but I also know people who think 9/11 was an inside job yet reject the idea of a massively criminal global health scam across the past four years. Everyone has different standards of truth…or truthiness. You and I are mostly in agreement on the distinctions, but it’s all over the map with everyone else! That’s why it’s so important there be uncensored public discussion on the respective truths of such matters, both online and off.

In any case, ‘conspiracies’ can be analyzed using semi-objective measures. Researcher Iaian Davis has put together a fairly comprehensive mapping of how policy-making bodies, mass media, think tanks and NGOs promote the interests of global corporations and the associated billionaire class, often without the consent or even knowledge of the governed, of course. For their part, Lance deHaven-Smith From Florida State University And Matthew T. Wit from the University of La Verne sidestep the scarlet letters of CT by invoking the term ‘SCADs”(State Crimes Against Democracy).

Smith and Wit define SCADs as “actions or inactions by government insiders intended to manipulate democratic processes and undermine popular sovereignty. Watergate and Iran–Contra are well-known examples of SCADs involving top officials. SCADs in high office are difficult to detect and successfully prosecute because they are usually complex and compartmentalized; investigations are often compromised by conflicts of interests; and powerful norms discourage speculation about corruption in high office.”

That’s a pretty good definition of ‘conspiracy’ as well. And no ‘theory’ required!

Monika Ullmann: A favourite example of mine is the weird and wonderful world of UFOs and how the US government, decided to ‘handle’ it by stonewalling, secrecy, lying and wholesale threats. In spite of recent so-called revelations and even the release of radar images tracking the bizarre movements of alien craft shadowing airliners and jet fighters, we are still utterly confused and uncertain about what’s going on. Some people even believe that the entire thing is a conspiracy to hide vastly superior secret weapons that are getting tested as so called UAPs, or Unidentified Flying Objects. I believe they changed the name because UFOs are, you guessed it, a crazy Conspiracy Theory and even SCADS couldn’t deal with it.

(More in Part 2)

I've heard an explanation for the Descartes dictum "I think therefore I am" being that with radical doubt about every bit of sense data coming into consciousness, the only thing you can be sure of is consciousness itself. Is that a good way to walk through the world? I think it's quite possibly the best way to walk thorough the world. It's a very Pure Mind Zen-like attitude. It doesn't mean you won't get duped; again, and again, and again. It just means that you won't mind so much, untethered, as you are, from any final explanation of the whole shebang. David Icke's absolutely 100% right though, I just have to say.

Great read. Loved the walled garden metaphor, powerful. Conspiracy theory itself, as a popular term, being created by conspiracy is brilliant.