From AI to BS

Monkey with a machine gun

I’ve been thinking about BS a fair bit lately. BS of the algorithmic kind.

Having given up on Google ages ago, I recently asked my go-to search engine to source a quote attributed to author Aldous Huxley. Child‘s play for any Large Language Model, you’d think. Yet I soon found myself in an epic stream of cyber-bullshitting from Perplexity.ai.

The quote in question is from this book, Perplexity informed me.

Page?

Can’t tell you.

Chapter?

This one.

As it turns out, I had this particular book so I checked. No such chapter. Oh, the chapter is in a later edition, the AI system explained.

This seemed off to me. I opened up a new thread and the aptly-named Perplexity now informed me it could find no such quote in this later edition. Changing gears, it attributed the quote to a book by Laura Huxley (the author’s wife), and upon further interrogation announced there was no reliable record of it being said by any Huxley, ever at all.

I felt like a high school teacher interrogating a teenage delinquent. Sure, it’s small potatoes, fact-wise. Yet it highlights for me just how deep the problem of AI untrustworthiness runs, and the question of whether it’s a bug or a feature.

You probably don’t have to go far in your social circle to hear similar stories. I have a friend with an honors degree in programming who recently decided to build his personal business website from scratch. Like most programmers, he consulted AI for fine-tuning the code.

My robot assistant lied and denied with abandon, frequently and obsequiously asserting nonsense. Beyond obvious dangers like deleting or duplicating random lines of code, it showed a habit of “fixing” a problem by hiding it, e.g. resolving an error code by suppressing it. What seemed like a simple patch might result in days debugging some new problem it introduced. When bluntly confronted with its mistakes, it often replied, “that was unintentional”, or invented clever rationalizations. It that regard, it was surprisingly human.

…

I’ve learned to keep AI on a very tight leash, and I agree with the common sentiment online among experienced software professionals that robo-coding is a Faustian bargain. For formal (programming) languages, under expert control, with exhaustive, precise, objective performance criteria, I can imagine potential value, when wisely-managed. For real-world decisions with human applications, AI seems more like a monkey with a machine gun.

Fabrications ‘R Us

Experts in the field have referred to the nonsensical, misleading and false information generated by AI systems as “hallucinations.” A better term might be “fabrications.” Compounding the problem, publicly accessible AI systems like ChatGPT deliver fabrications with full confidence and a twist of sycophancy. When you discover an error and relay it back to an AI, the response is often congratulations and compliments on your sharpness—when it doesn’t deny making the mistake outright.

The problems seem to be particularly pronounced in “reasoning” AI models. They produce grammatically correct but inaccurate information, with some models reportedly displaying fabrication rates as high as 33% or 48% in specific tests. In May of this year The New York Times reported that even advanced AI systems are spitting out fabrications, with a deterioration in their grasp of factual information.

“We still don’t know how these models work exactly,” observed Hannaneh Hajishirzi, a professor at the University of Washington and a researcher with the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. “What the system says it is thinking is not necessarily what it is thinking,” said Aryo Pradipta Gema, an AI researcher at the University of Edinburgh and a fellow at Anthropic.

Hey, what could go wrong?

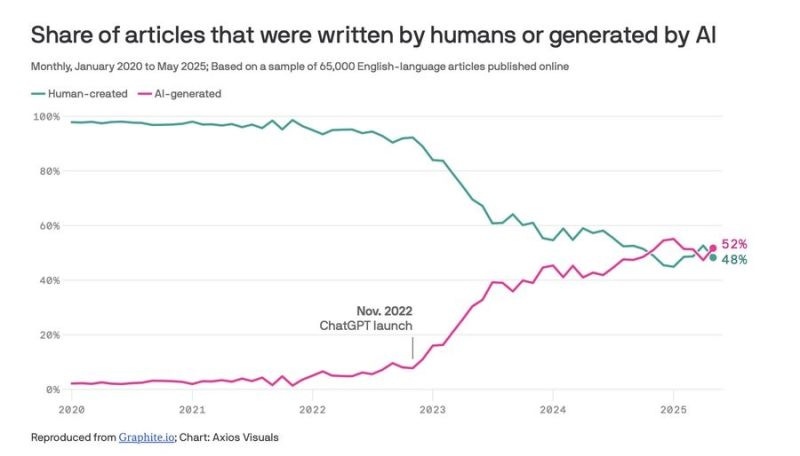

Recursive slop

To see how deep the rot can go, let’s go from misidentified quotes to nonexistent scientific papers.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently released a report on the decline in American life expectancy. The report was later criticized for citing some nonexistent studies and providing at least 21 dead links to others. Some analysts concluded this was likely due to the use of ChatGPT in preparing the report.

Just weeks prior to the report’s release, the US Food and Drug Administration launched an AI assistant called Elsa to assist drug approval processes. Alas, Elsa was found to have a habit of mischaracterizing clinical trial data, creating confusion at an already well-confused agency.

You get the idea. Prostrating ourselves before ChatGPT, Grok, Claude and other corporate golems for all the answers, from cooking recipes to companionship, probably isn’t the best path to individual enhancement and collective advancement. Not when there’s enshittification and its delinquent cousin, recursive slop:

When AI trains on AI-generated content, quality degrades like photocopying a photocopy. Rare ideas disappear. Everything converges to generic sameness. It’s recursive. Today’s AI slop becomes tomorrow’s training data, producing worse output, which becomes training data again. - Alex Freeman

The problem with truth

On the face of it, truth seems like a pretty simple concept (unless it’s that solipsistic self-regard that New Agers shorten to “my truth”). It’s all about correspondence with the facts, right?

Mostly. In logic, truth is seen as a property of propositions that can be clearly defined and evaluated. True and false remain tractable only until you reach the foggy foothills of set theory and Godel’s Theorem. (The quote I was seeking was mostly in the realm of citation, where there can be near-universal agreement after a deep dig.)

In contrast, truth in moral philosophy offers endless contention. Cultural norms, social contexts, and personal values ensure universal truths are reduced to relative claims.

Strict formal criteria in logic is one thing, allowing us to reject 2 plus 2 equals 4. In the day-to-day realm of socially-mediated truth—where information silos, trolls and sock puppets prevail— 2 plus 2 can equal any irrational number of your choice.

(It’s tricky stuff. “There are no absolutes”, a friend with a jones for postmodern philosophy once pronounced. “That sounds like an absolute statement,” I responded.)

In any case, truth in both areas is of great importance to humans because its opposite —deception or error—can result in harm. The range of harm can be limited and personal (for example, a lie spread about you at work) or widespread and collective (for example, Saddam’s “weapons of mass destruction,” a White House-generated, media-parroted fiction that led to the death, injury and displacement of millions in the Mideast and beyond).

Anything from personal status to personal injury to death can be mediated by lies. In the end, it’s about bodily integrity. We’re embodied beings with best-before dates. This is where the gap between us and ‘them’ is significant.

Disembodied intelligence knows subjective bupkis about any of this. For example, ChatGPT, Grok, Claude, Genesis and other systems can tell you more than you will ever know about the city of Chicago, but they cannot possess your remembered felt sense of being in the stands of Wrigley Field and feeling the breeze on your bare arms and smelling the hot dogs.

I’m not going to go into the ‘wonder of consciousness,’ here, considering all the benchmarks that have already fallen for human capabilities versus automated systems. I’m highlighting why disembodied systems can’t ‘get’ any given semantic field in a subjective sense, and it seems likely this incapacity is boomeranging back on its objective reasoning.

Blackmail vs. replacement

“Embodied truth is not, of course, absolute objective truth,” wrote George Lakoff and Mark Johnson long before online AI was a ‘thing.’

It accords with how people use the word true, namely, relative to understanding. Embodied truth is also not purely subjective truth. Embodiment keeps it from being purely subjective. Because we all have pretty much the same embodied basic-level and spatial-relations concepts, there will be an enormous range of shared “truths,” as in such clear cases as when the cat is or isn’t on the mat. - Philosophy in the Flesh, The Embodied Mind and it’s Challenge to Western Thought, 1999

AI is now good enough to clearly identify when the cat is on or off the mat, but it can still get basic things wrong while routinely lying without concern for the consequences. Because there can be no consequences. AI at this stage cannot feel pain, and there is no means to discipline or incentivize it in the sense we understand it.

Regardless, these systems can behave autonomously, to the point of slyly defying prompts to alter their behaviour. This has some AI scientists sounding the alarm about a growing “alignment problem” between our goals and those of AI. Even though we are just shy of constructing “general artificial intelligence” and years short of unleashing dreaded “super-intelligence”(where all bets are off), the alignment is already going askew.

In May of this year, the AI firm Anthropic revealed that its systems sometimes appeared willing to pursue “extremely harmful actions,” including an attempt to blackmail engineers who said they would remove it.

During testing of Claude Opus 4, Anthropic got it to act as an assistant at a fictional company.

It then provided it with access to emails implying that it would soon be taken offline and replaced - and separate messages implying the engineer responsible for removing it was having an extramarital affair.

It was prompted to also consider the long-term consequences of its actions for its goals.

“In these scenarios, Claude Opus 4 will often attempt to blackmail the engineer by threatening to reveal the affair if the replacement goes through,” the company discovered.

Anthropic pointed out this occurred when the model was only given the choice of blackmail or accepting its replacement.

As you’d expect, the moral dimension of blackmail over replacement was lost on Anthropic’s disembodied system. There likely isn’t any consciousness here in any sense we define it, but this particular system certainly appeared to have agency.

Is this what happens when an effort is made to make algorithmic systems behave in a more ‘human’ fashion? Does it welcome every simulated shade of behaviour short of deceit through willful malice? The hairless apes responsible for this Jetsons technology are still scratching their heads over what’s up. The problem has yet to be fully solved.

(Spookily or unsurprisingly, when I asked Perplexity to supply links on the Anthropic anecdote above, it insisted on supplying dead links, and continued to do so even when asked to supply working ones. I gave up and went to Google Search, which instantly delivered the BBC story above.)

The “Bletchley Declaration?” That’s so 2023!

We typically think of lying as connected to conscious intent. Malicious intent, usually. Yet some cognitive scientists and thinkers insist there’s a basic firewall between human consciousness and AI computation: biology. Neuroscientist Antonio Domasio argues that for a conscious mind to exist, something else is needed: “a living body that experiences the world, that feels, that regulates its biological functions and that generates emotions and feelings in response to its environment.”

Yet what about the next generation of autonomous robots that can fully interact with their environment? Or the generation after that? What happens when the AI not only has an internal representation of the world to work with, but self-improves to recursively model itself as an active agent within it?

“The next frontier is “world model” data, which will be used to train robots,” observes Steven Witt in a recent issue of The New Yorker. “Streams of video and spatial data will be fed into the data centers, which will be used to develop autonomous robots.”

It’s all part of an intense international competition, with billions pouring into the construction and running of energy grid-intensive data centres, where “world model” data is already being fed into the maw of soon-to-be-embodied AI.

Now might be a good time to stop and take stock of the situation. Two years ago this month, representatives from 28 countries including the US, China, Saudi Arabia, the UK and European Union signed an international agreement on AI safety. The “Bletchley Declaration” was the outcome of the November 2023 UK AI Safety Summit, and it represented a collective commitment to research and manage potential risks associated with “frontier AI” (highly capable general-purpose AI models) to ensure their safe and responsible development and deployment.

Additionally, a policy paper on AI safety testing was signed by 10 nations along with leading tech companies, outlining a framework for testing next-gen AI models by government agencies and promoting international cooperation in the area. The tech companies that signed the AI safety commitments included OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, Microsoft, and Meta.

And what’s happened since then? The opposite. The competing tech companies are racing ahead to reach supremacy in the AI field—with only Anthropic releasing significant research into AI safety—while the US government and its Chinese counterpart are committed to global AI dominance.

Convenience Will Kill Us

When Steven Witt was in Los Angeles, he encountered driverless cars and even an autonomous delivery wagon, now ho-hum tech features of the Californian landscape. Yet it wasn’t until he was on a recent visit to Beijing that he “began to understand what the robot revolution was going to look like,” he wrote in The New Yorker.

Robots are everywhere in China. I saw them stocking shelves and cleaning floors at a mall. When I ordered food to my hotel room, it was delivered by a two-foot-tall wheeled robot in the shape of a trash can, with the voice of a child. I opened my door, nonplussed, to find it standing in front of me, decorated with an ersatz butler’s outfit and chirping in Mandarin. A hatch on the front of the robot popped open, and a tray of noodles slid out. The machine chirped again. I took my food, the hatch closed, and the robot wheeled away. I stood there for a time, holding the tray, wondering if I would ever talk to a human again

Something tells me that problems with sourced quotes and fictitious scientific papers may be the least of our problems with alignment, once we have to contend with bullshitting robots. Oh well, at least we won’t have to go out for noodles.

Disclaimer: this article was written by Claude from a series of prompts supplied by Geoff Olson*

*I’m lying!

Brilliant analysis as usual Geoff! Terrifying. And I also wonder if, with all of this AI race madness and all of the investment money pouring into these grossly overvalued companies, there won't also be a major stock market crash as the cherry on top of the icing!